The coronavirus utilizes this protein to attack human cells.

Specialists overall are dashing to create potential immunizations and medications to battle the new coronavirus, called SARS-Cov-2. Presently, a gathering of analysts has made sense of the sub-atomic structure of a key protein that the coronavirus uses to attack human cells, possibly opening the entryway to the advancement of an antibody, as indicated by new discoveries.

Past research uncovered that coronaviruses attack cells through supposed “spike” proteins, however those proteins take on various shapes in various coronaviruses. Making sense of the state of the spike protein in SARS-Cov-2 is the way to making sense of how to focus on the infection, said Jason McLellan, senior creator of the investigation and a partner teacher of atomic biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

Despite the fact that the coronavirus utilizes a wide range of proteins to reproduce and attack cells, the spike protein is the significant surface protein that it uses to tie to a receptor — another protein that demonstrations like an entryway into a human cell. After the spike protein ties to the human cell receptor, the viral layer wires with the human cell film, permitting the genome of the infection to enter human cells and start disease. So “in the event that you can forestall connection and combination, you will forestall section,” McLellan disclosed to Live Science. Yet, to focus on this protein, people have to comprehend what it resembles.

Not long ago, scientists distributed the genome of SARS-Cov-2. Utilizing that genome, McLellan and their group, as a team with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), recognized the particular qualities that code for the spike protein. They at that point sent that quality data to an organization that made the qualities and sent them back. The gathering at that point infused those qualities into mammalian cells in a lab dish and those phones created the spike proteins.

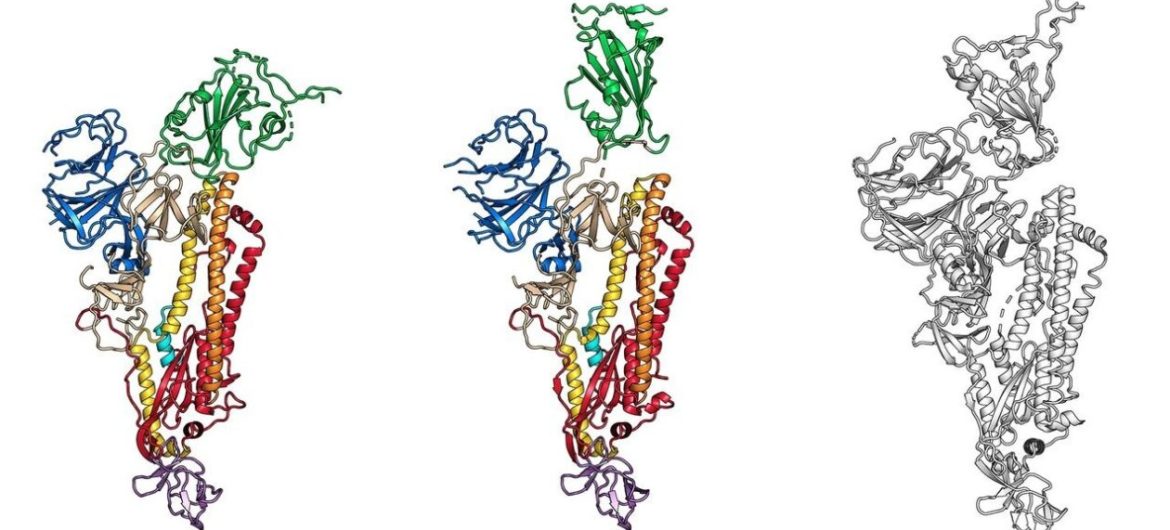

Next, utilizing an extremely point by point microscopy system called cryogenic electron microscopy, the gathering made a 3D “guide,” or “diagram,” of the spike proteins. The outline uncovered the structure of the particle, mapping the area of every one of its molecules in space.

“It’s noteworthy that these specialists had the option to get the structure so immediately,” said Aubree Gordon, a partner teacher of the study of disease transmission at the University of Michigan who was not a piece of the examination. “It’s a significant advance forward and may help in the improvement of an immunization against SARS-COV-2.”

Stephen Morse, an educator at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health who was likewise not a piece of the examination concurs. The spike protein “would be the imaginable decision for fast advancement of antibody antigens” and medicines, they disclosed to Live Science in an email. Realizing the structure would be “extremely useful in creating immunizations and antibodies with great movement,” as would delivering higher amounts of these proteins, they included.

The group is sending these nuclear “organizes” to many research bunches far and wide who are attempting to create antibodies and medications to target SARS-CoV-2. In the mean time, McLellan and his group would like to utilize the guide of the spike protein as the reason for an immunization.

At the point when remote trespassers, for example, microorganisms or infections, attack the body, insusceptible cells retaliate by creating proteins called antibodies. These antibodies tie to explicit structures on the remote intruder, called the antigen. In any case, delivering antibodies can require some investment. Immunizations are dead or debilitated antigens that train the resistant framework to make these antibodies before the body is presented to the infection.

In principle, the spike protein itself “could be either the immunization or variations of an antibody,” McLellan said. At the point when you infuse this spike-protein-based immunization, “people would make antibodies against the spike, and afterward on the off chance that they were ever presented to the live infection,” the body would be readied, they included. In view of past research they did on different coronaviruses, the specialists presented transformations, or changes to make an increasingly steady particle.

Without a doubt, “the molecule looks really good; it’s really well behaved; the structure kind of demonstrates that the molecule is stable in the correct confirmation that we were hoping for,” McLellan said. “So now we and others will use the molecule that we created as a basis for vaccine antigen.” Their partners at the NIH will currently infuse these spike proteins into creatures to perceive how well the proteins trigger counter acting agent creation.

All things considered, McLellan thinks an antibody is likely around 18 to two years away. That is “still quite fast compared to normal vaccine development, which might take like 10 years,” they said.

Disclaimer: The views, suggestions, and opinions expressed here are the sole responsibility of the experts. No Times World USA journalist was involved in the writing and production of this article.